Rich-CRDTs are conflict-free data types (“CRDTs”) extended to provide additional (“Rich”) database guarantees. These guarantees, such as constraints and referential integrity, make building local-first applications much simpler.

In this post, we introduce Rich-CRDTs, walk through the techniques they use and show some concrete examples.

Refresher on CRDTs

As a brief refresher: CRDTs are special data types that give us conflict-free concurrency. Using CRDTs, multiple people can update the same data at the same time. All their updates will be merged without conflicts and they will all end up with the same value. This is strong eventual consistency (once all the updates are replicated, everyone converges on the same data) and CRDTs are a key ingredient of both modern low-latency geo-distributed databases and multi-user collaboration systems.

CRDTs encode a conflict resolution policy that merges concurrent updates. When two nodes of a distributed system try to update the CRDT at the same time, the CRDT uses the encoded method to merge the operations. The merge method must meet certain mathematical requirements: commutativity, associativity, and idempotency.

There are many different types of CRDTs, for example:

- Counter: the merge method adds up the values of all the operations

- Last-Writer-Wins Register: the merge method simply sets the register with the value of the operation with the latest timestamp

CRDTs can be composed to form more complex objects. However, getting the merge strategy and consistency semantics right can be very challenging. For example, some operations can’t be merged together without breaking consistency and many common database invariants can’t be guaranteed by the merge strategy of individual data types.

It’s rare to build a modern application with CRDTs without encountering these sorts of composability and invariant safety issues, but solving them is still an ad hoc process. Every time a developer builds a new application with CRDTs, they have to reason about these issues and make decisions from scratch. This lack of standardization makes coding with CRDTs error-prone.

The goal of Rich-CRDTs, then, is to provide developers with higher level abstractions with built-in checks and defaults that work “out of the box”.

Rich-CRDTs

Rich-CRDTs provide additional invariant safety and database guarantees on top of basic CRDTs. They do so by using a range of techniques:

The first two techniques -- composition and compensations -- are conflict-free. They work without introducing additional coordination mechanisms. The third technique -- reservations -- aims wherever possible to avoid runtime coordination but falls back on it as a last resort to guarantee invariants where necessary.

Individual rich-CRDTs can use one or more of these techniques together. The high level approach when designing a rich-CRDT is to try to preserve the desired invariant(s) using the conflict free techniques and to use reservations sparingly where necessary.

┌────────────────────────┐

│ │

│ Can I use basic CRDTs? ├──► Done

│ │

└──┬─────────────────────┘

│

▼

┌────────────────────────┐

│ │

│ Can I use composition? ├──► Done

│ │

└──┬─────────────────────┘

│

▼

┌──────────────────────────┐

│ │

│ Can I use compensations? ├──► Done

│ │

└──┬───────────────────────┘

│

▼

┌────────────────────────────────┐

│ │

│ Can I use escrow reservations? ├──► Done

│ │

└──┬─────────────────────────────┘

│

▼

Use lock based reservations

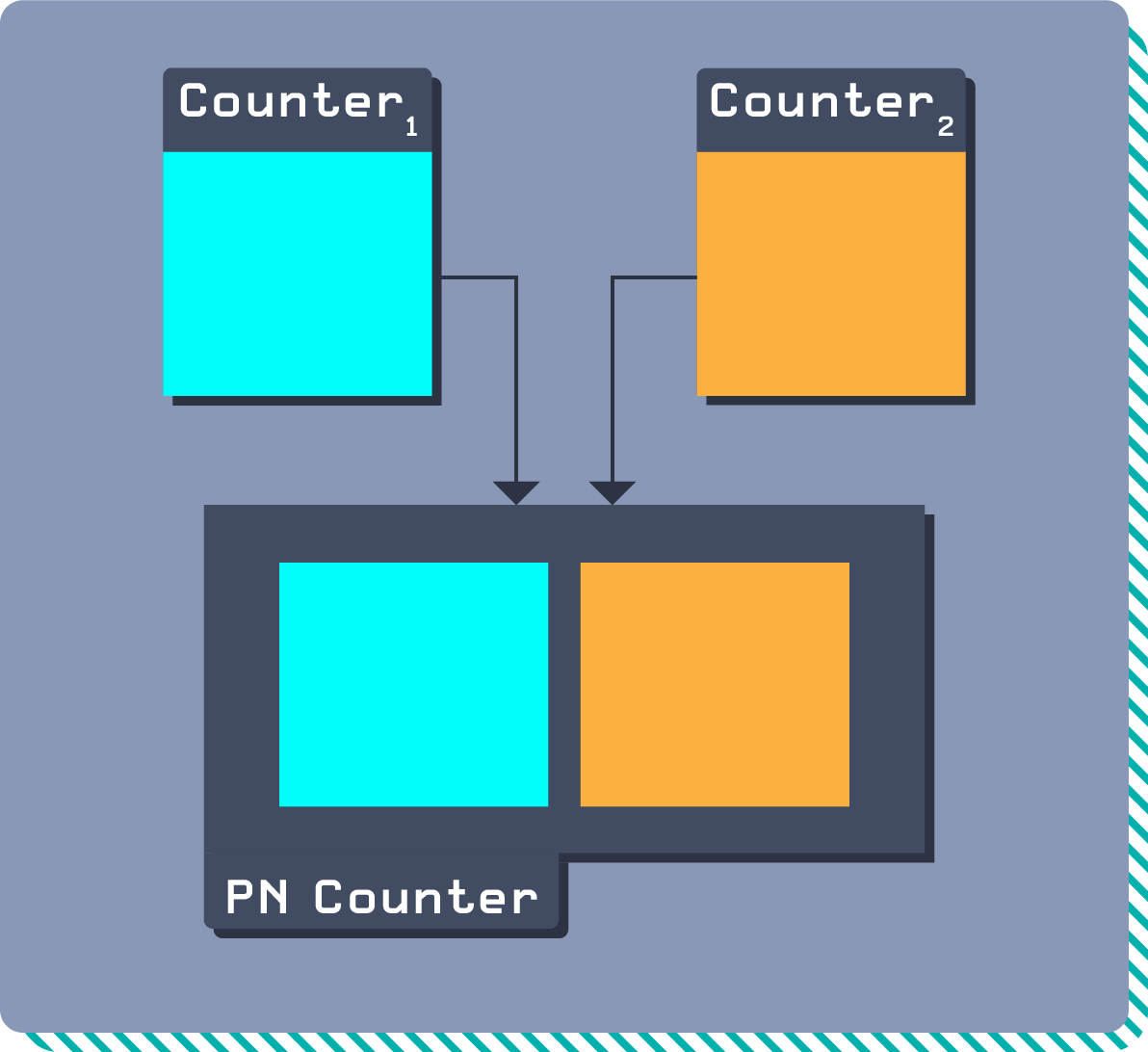

Composition

Composition refers to combining or nesting CRDTs to create richer, higher-order conflict-free data structures.

A simple example of CRDT composition is a Positive Negative Counter, or PN Counter. A PN Counter combines two counters: one counts positive changes and one counts negative changes. The PN Counter then combines these two counters to give the net current value.

A more complex example is a JSON CRDT. JSON is in essence a map made up of four data types: string, number, object, array. In a map CRDT, each key can contain a different CRDT object as its value. The JSON CRDT provides sensible defaults for each possible value type provided by JSON.

For example:

{

"name": "Valter",

"score": 234,

"attributes": {

"location": "Lisbon"

},

"history": [

"bought-fish",

"grilled-fish"

]

}

Each key in this JSON CRDT maps to a different primitive CRDT type, and different conflict-resolution strategies might be used for each type. For instance name could use Last-Writer-Wins, score could use a Counter and history could use an array type (such as a Replicated Growable Array). A map might additionally provide a conflict-resolution strategy for when operations associate values of different types to the same keys.

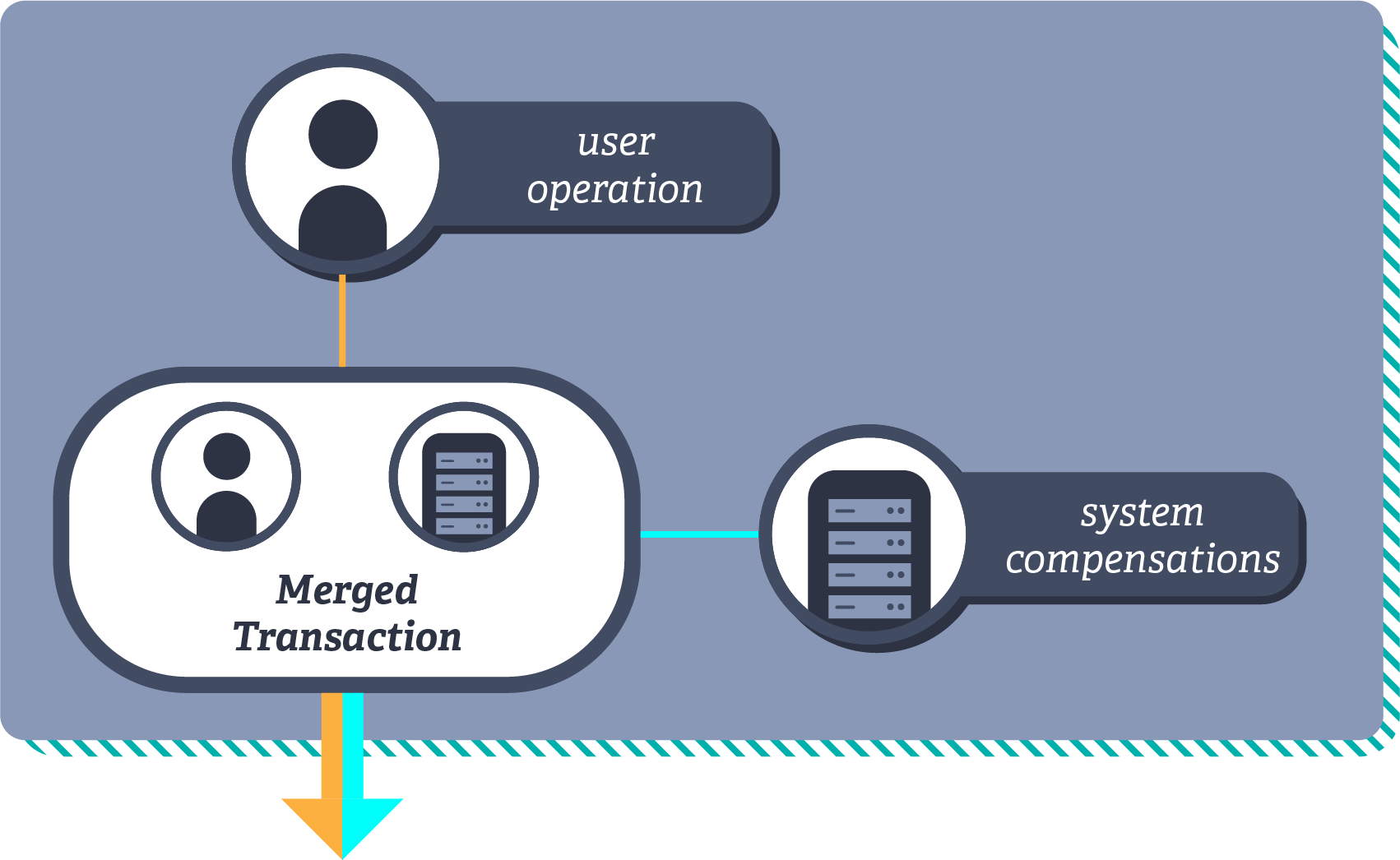

Compensations

Compensations refer to additional operations undertaken by a database (other than the operations specified by the user) that ensure it will maintain an invariant.

In databases, you often have multiple tables linked together by keys – the foreign key in the associated table, which corresponds to a primary key in the parent table. Referential integrity is about making sure that these links are valid at all times. I.e.: that if you delete row 15 in a primary table, there’s no foreign key in any related table with the value of 15.

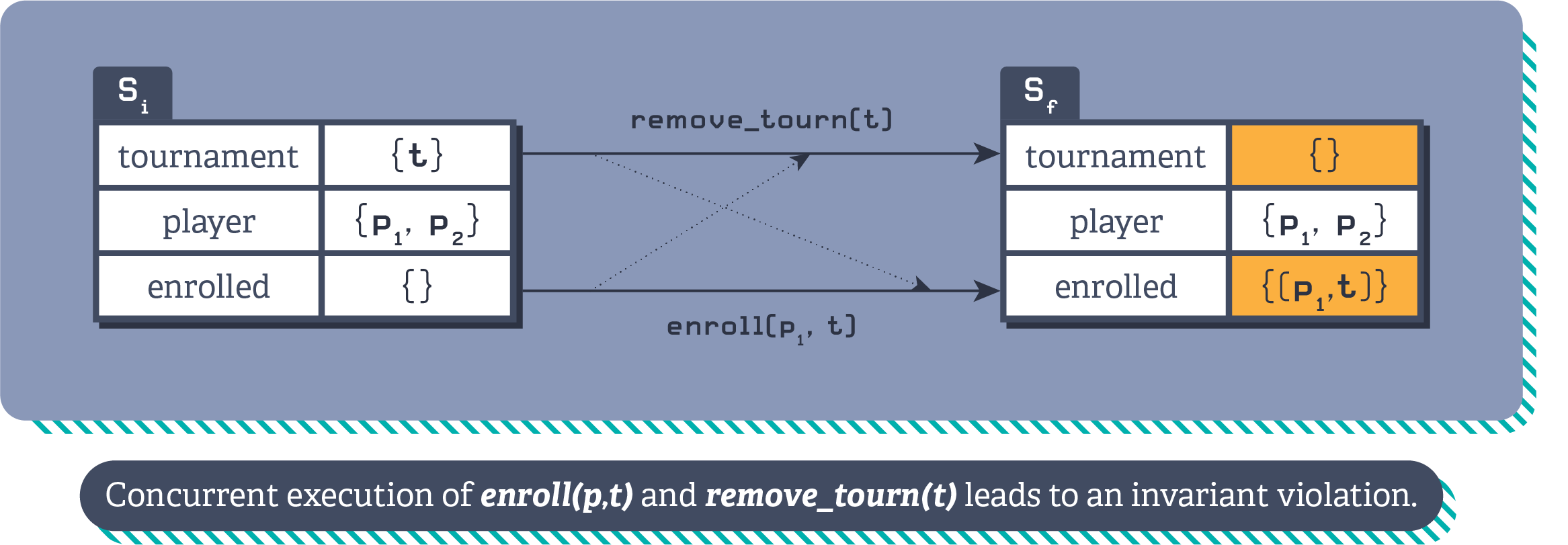

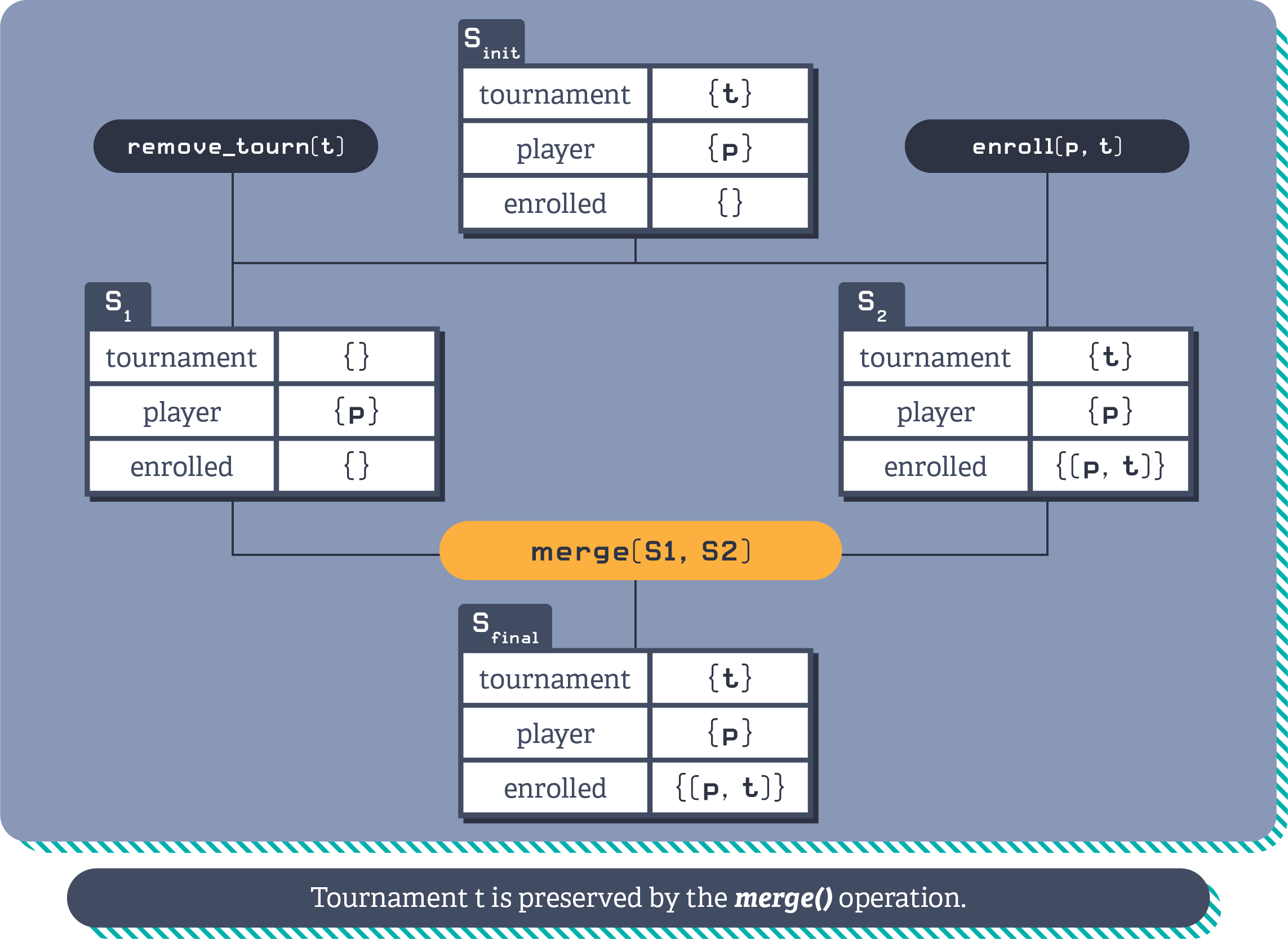

Referential integrity poses challenges when it comes to concurrent operations, because one operation might delete a row at the same time that another row is being added to an associated table that refers to it. A classic example is a player being enrolled in a tournament concurrently to the tournament being deleted.

Compensations can offer a solution. For example, by adding a touch operation to the enrol player operation. By adding the additional touch operation into the transaction where the player is being enrolled, it can ensure that the tournament still exists, even when merged with a concurrent transaction removing the tournament, if the set of tournaments follows add-win semantics.

In the absence of conflicts, these additional effects are not observable.

You can play with an interactive demo of this example on the Introduction -> Active-active replication page.

Reservations

Reservation refers to enabling concurrent operations on a single data type by “reserving” a certain amount of resources for each client. Resources can be reserved in three ways:

Escrow

Escrow reservations are a class of reservations in which the resources acquired for an operation are shared out across a distributed cluster, so that individual nodes and clusters posses a share of "rights" to perform certain operations.

A bounded counter is an example of a Rich CRDT that uses the reservations technique. The bounded counter pre allocates a fraction of the resources to each node. For example, suppose you’re Stubhub and you have 1000 tickets to a Justin Bieber concert to sell. You want to avoid a scenario where two people both buy the last concert ticket on two different nodes.

You give each of 10 nodes an allocation of 100 ticket reservations. When any given node runs out of its allocation of tickets, it can coordinate with other peers to get more reservations. In this way, it’s possible to validate an operation without having to coordinate every time.

One of the key optimisations with escrow reservations is to proactively allocate and re-balance the reservations so they are held by the nodes/clusters that require them. If the Justin Bieber concert is in San Francisco and all the tickets are being bought through the US-West cluster, then the rich-CRDT system can notice (or predict) this and pro-actively give the US-West cluster more reservations.

In many cases, when working effectively, proactively rebalancing reservations can avoid coordination for the vast majority of updates.

Escrow plus algorithm

Escrow plus algorithm reservations are a class of reservations in which the resources acquired for an operation are given by an algorithm.

For example, operations on a tree structure need to be carefully executed to maintain the tree invariant. For instance, two nodes can concurrently be moved one under the other, introducing a cycle.

One can reserve the root of a tree to safely execute move operations, preventing any other concurrent operation on the tree. However, A reservations algorithm can be more efficient. Concurrent operations on a tree structure are safe as long as operations touch different parts of the tree. The arguments of the move operations, source and destination, can be used to compute the closest parent that needs to be reserved to ensure the nodes can be moved safely and still allow concurrent operations on other subtrees.

Locking

Locking refers to a technique where only the node holding the lock is able to access a certain resource. Some locks are shared and some are exclusive.

For example, global sequential identifiers need to be generated one-at-a-time and in sequence, i.e knowing the last generated value globally, so that they preserve the sequential property without gaps.

To do this, developers might make use of a lock CRDT. When a particular node holds the lock, it’s able to 1) see the changes produced by the previous lock holder, and so knows what the next identifier in the sequence should be, and 2)is able to access the portion of code that generates the global identifier. Otherwise, it must exchange permissions with other peers, similar to the escrow mechanism explained above.

Next steps

Hopefully that was a useful intro to rich-CRDTs and how they can help simplify working with invariants and complex data objects. ElectricSQL uses rich-CRDT techniques to provide support for referential integrity and constraints in a local-first setting. See the reference docs for more information.